In September 2015, the Ukrainian startup community and technology-focused media went into a frenzy after Snapchat announced it was acquiring Looksery, an Odessa-based image-processing startup.

The deal, reportedly valued at around $150 million, represented one of the most spectacular startup success stories to emerge from Ukraine to date.

Looksery’s app could change anyone’s face in real time — using fun animations while having a video chat with someone, for example, or doing things like removing blemishes and altering eye color. The company was founded by Victor Shaburov, a serial entrepreneur and active supporter of programming contests for talented youth.

In 2013, Shaburov met Yuri Monastyrshyn, a fourth-year student in Odessa who would become the COO of Looksery. The product team was hired in Sochi, Russia, when the two nations enjoyed more peaceful relations. After the acquisition, the Looksery team relocated to Silicon Valley to work together with their new Snapchat colleagues.

Eastern European tech for Silicon Valley giants

Looksery was the first in a series of success stories involving computer vision and facial recognition startups from Eastern Europe.

Six months later, in early 2016, Facebook bought Masquerade, the Minsk-based developer behind another video filter app, MSQRD, which was at one point one of the most popular apps in Apple’s App Store. Facebook described MSQRD as “a fantastic app with world-class imaging technology for video.”

A little more than a year later, another Belarusian company, AIMatter, was snapped up by Google, just months after raising $2 million from local investors. Its SDK (software development kit) for real-time photo- and video-editing on mobile, dubbed Fabby, was touted as being faster than other available solutions. One of Fabby’s neat features — built upon a neural network-based AI platform — allows users to separate an object from its original background.

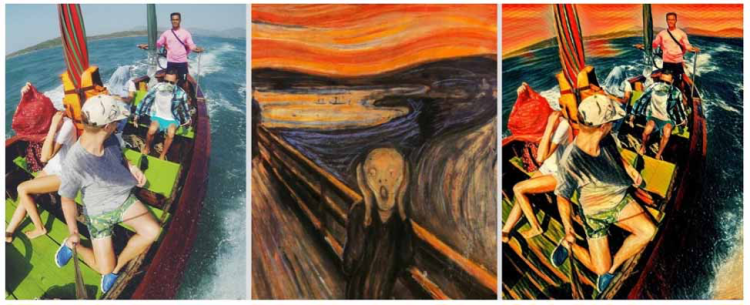

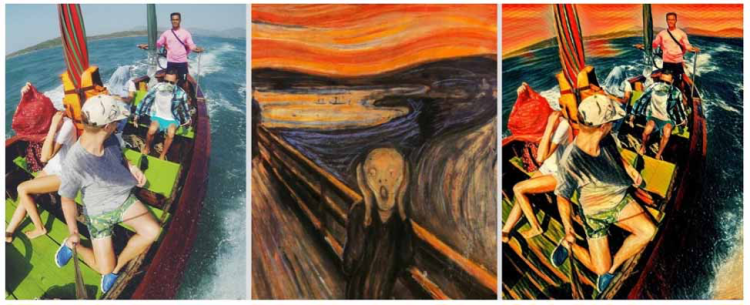

Russian startups are hot, too. Last year, an app made by Alexey Moiseenkov, an employee of the Mail.Ru Group, became a regional hit before surging up the global app store rankings. Called Prisma, the app — also built on neural networks — invites users to add stunning artistic effects to their photos to make them look like works of art.

The approach was not new (see DeepArt.io, based in Germany, and Ostagram, a Russian project created by Sergey Morugin), but Prisma’s distinctive advantage was in its speed and mobile-focused format.

Above: Prisma can transform your photos into artworks modelled on iconic paintings such as Edvard Munch’s’ “The Scream”

In 2017, Prisma launched Sticky, a new app that turns selfies into stickers for sharing in your social feeds. The company is still independent, but recent rumors have suggested that Facebook and Snapchat were eyeing it for a potential acquisition.

The roots of excellence

Developing computer vision technologies for mobile isn’t just a simple case of mathematics. Optimizing performance is important, given the limited processing power of many modern mobile devices.

“Nobody needs an AR app which will work only on iPhone X,” noted Viktor Prokopenya, a serial entrepreneur with Belarusian roots who recently launched a $100 million investment program for AI startups. “There are billions of devices in the world, and a very small percentage of them are expensive devices. If you want to make a mass market mobile application, it should work on an iPhone 5s and give 30 frames per second, which is a challenge in its own right.”

The talents of East European engineers working to solve such an array of technological challenges can be traced in part to an education tradition dating back to the Soviet era. For all its moral and economic failures, communism demonstrated a rare capacity to raise generations of brilliant scientists and engineers that span several domains.

“In the field of machine intelligence, the Markov chains, Markov random field, and Markov models are the very basis of deep learning, while the Hidden Markov Model (by Ruslan Stratonovich) is the main model for speech recognition,” said Alexander (Sasha) Galitsky, a prominent Russo-Ukrainian investor who invests globally through the Almaz Capital fund. “Alexey Ivakhnenko, who was a prominent Soviet and Ukrainian mathematician, is still referred to as the father of deep learning.”

While the Soviet regime collapsed, the local mathematics education system was preserved to a large extent.

“The transformation went gradually, in an evolutionary way,” added Alexander Kurbatsky, professor of the computer programming department of the Belarusian State University in Minsk. “Thus, good math education created a nurturing environment for today’s digital transformation, which goes beyond the territory of the former Soviet Union,” he continued, referring to the many thousands of IT engineers and entrepreneurs who have moved to Silicon Valley, Berlin, Israel, and even Asia over the past 20 years.

Next-gen startups with “empathic cameras”

A considerable number of these IT talents still live and work in the Eastern Europe region, however, with new players springing up in facial recognition and related AR technologies.

After the Facebook acquisition, two former MSQRD team members, Andrey Yanchurevich and Dmitriy Dorin, launched AR Squad, a startup dedicated to “next-gen AR content.”

“Funny masks were a part of MSQRD’s viral strategy,” the company proclaims. “Today, we are developing a new level of interaction between users and augmented reality.” The young company has hired MSQRD’s whole art team, as well as additional experts from this field, and serves clients from the U.S., Russia, and Belarus.

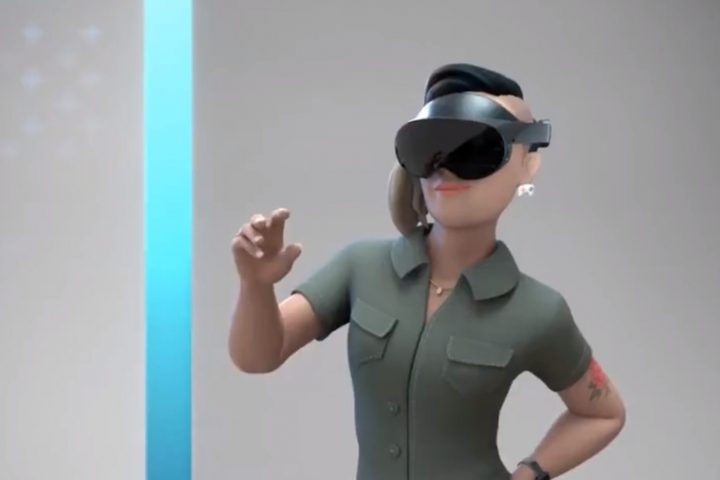

Banuba, a startup born in Belarus but operating worldwide from its Hong Kong and Cyprus offices, recently developed an AR mobile software development kit for app developers and publishers worldwide. To a large extent, this technology relies on AI algorithms to recognize people’s faces and bodies; understand their emotions, facial expressions, postures, and gestures; and estimate race, age, and gender.

The solution can be used in a variety of apps — from content suggestions that improve your mood to very practical recommendations — for example, which hairstyle suits you best, or how you will look in the future. According to the company’s CEO, Vadim Nekhai, Banuba’s advantages lie in its “capability of mixing technologies on the same device and optimizing them for ground-breaking performance results.”

In early 2017, Banuba secured $5 million from Prokopenya and his investment partners. Following this, the startup launched a “technology-for-equity” program to enroll app developers and publishers across the world.

The first such agreement was signed with Inventain, another startup from Belarus, to develop AR-based mobile games. A special purpose vehicle (SPV), dubbed Camera First, was created with a $1.2 million capital injection from Banuba to develop the games.

Above: How Banuba technology maps and analyses a smiling face

The implications of mobile AI and AR technologies extend far beyond making gimmicky pictures and video features. “Such technologies can be leveraged by virtually every kind of app,” said Prokopenya.

Prokopenya envisions a world where “any app can characterize its users through the camera: male or female, age, ethnicity, level of stress, etc,” he added. “Content can then be optimized for maximum performance, based on such parameters.”

Thus, fitness apps can see how much weight you’ve gained or lost by analyzing your face, while games can adapt their pricing models to suit the type of user. Rather than viewing such applications as an intrusion on users’ privacy, Prokopenya sees something “empathic” in them. “They will understand the kind of emotions your face is showing and adjust their content correspondingly,” he said.

In the commercial realm, facial recognition software has been developed by Russian startup VisionLabs. The solution, dubbed Face_IS, allows retailers to make personalized offers to customers whose faces have been recognized. The technology may also be applied to ad personalization, user identification in internet of things (IoT) projects, medicine, transportation, and virtual / augmented reality.

Another VisionLabs solution, Luna, allows businesses to “verify and identify customers instantly” based on images, thanks to a “unique quality and performance pattern recognition technology.”

This technology has attracted the attention of Google and Facebook, which have supported VisionLabs’ efforts to develop professional communities in computer vision and neural networks.

The good, the bad, the ugly

Another promising but controversial technology from the region is FindFace. It was launched in 2015 by Moscow startup NTechLab, which presented it as “the world’s most accurate facial recognition technology for face detection, verification, and identification.”

FindFace is built on a deep learning and a neural network-based architecture. In November 2015, NTechLab won the MegaFace Benchmark, a world face recognition championship held in the U.S. The challenge was to recognize as many people as possible from a database of more than a million photos. The Russian startup bypassed more than 100 competitors, including Google, with its FaceNet program.

The app made headlines in Russia, where social media users use it to put names to faces using only a picture. Indeed, FindFace can match pictures with people’s profile images on Vkontakte, the country’s leading social network. The app is mainly being used for dating purposes, though it has also allowed police to identify criminals, and some have used it to harass young women. Nevertheless, the startup recently raised $1.5 million in a round led by Impulse VC, a venture fund that is reportedly affiliated with Russian billionaire Roman Abramovich.

Grigory Bakunov, director of technology distribution at Yandex, came up with a sort of antidote to such intrusive technologies. Taking time out of his day job, he developed an “anti-facial recognition algorithm” to conceal people’s identities with the help of makeup.

Above: Grigory Bakunov, the Yandex engineer who developed an “anti-facial recognition” solution

“The service was able to offer futuristic makeup that could trick smart cameras with just a few facial lines,” Bakunov said in an interview. The project proved short-lived, however, because Bakunov realized that it would now be possible to deceive banks and the police.

“That’s why we decided we shouldn’t launch it on the market,” he added. “The chance that someone might use it for nefarious purposes was too high.”

This story originally appeared on Www.ewdn.com. Copyright 2017

Source: Why Eastern Europe is a hotbed for computer vision startups